Mercantilism in the 21st Century

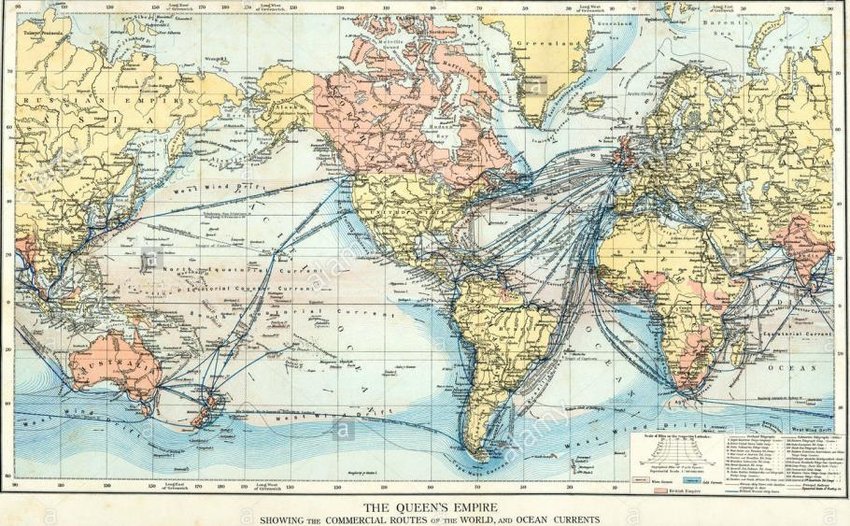

Mercantilism is an economic theory that dominated European policy from the 16th to 18th centuries. Nation-states emphasized exports over imports (EconLib) and actively intervened in the operation of their own economies, as well as those of other nations. Historically, the creation of the Hudson’s Bay Company and the British East India Company are frequently cited examples of this policy during that period. Both companies operated as global arms of the British government, advancing its economic health and standing both domestically and globally, often with protection from the Royal Navy to secure vital trade routes.

The 21st century has seen a resurgence of modern mercantilist policies, including protectionism, tariffs, and resource-driven geopolitics. Recent U.S. trade policy announcements have raised concerns among traditional trading partners, partly due to the more assertive and conspicuous tone of the U.S.. administration.[1]. However, it is not clear these policies will deliver the intended results.

Trump’s ‘America First’ agenda has been framed as a strategy to restore domestic manufacturing, reduce trade deficits, and position America as a global powerhouse. This is, effectively, a 21st-century re-statement of mercantilist thinking—where economic power is directly linked to political dominance. Geopolitical statements by Trump following his election, concerning Greenland, Canada, Ukraine, and key trade routes such as the Arctic and the Panama Canal, reflect classic mercantilist strategies. However, given the interconnected nature of global trade in the 21st century, this approach may ultimately undermine and weaken American influence, rather than “Make America Great Again”.

The Geopolitical Implications of Resource and Trade Route Control

Trump’s suggestion the U.S. was interested in acquiring Greenland was widely ridiculed at the time, but it underscores a broader theme within the Mercantilist school about resource security and strategic positioning. Greenland possesses significant rare earth mineral deposits, which are critical for modern technology and defense industries. Moreover, as Arctic ice melts, Greenland’s geographic position makes it a key gateway to emerging Arctic trade routes that could rival the Suez and Panama Canals.

Similarly, Ukraine’s vast mineral wealth, including lithium and rare earth metals, and its dominance in global agriculture make it a strategically valuable nation—both economically and geopolitically. The same logic applies to Canada, which holds significant reserves of oil, lumber, water and minerals. Statements from the Trump administration regarding U.S. access to these resources—through annexation, acquisition, or tariff programs aimed at reshoring production to the U.S.—reflect a deliberate effort to control key resources, which the U.S. is currently obliged to import from sovereign nations on an equal footing withother potential customers.

The Panama Canal, a major artery of global trade, remains another focal point of U.S. trade policy. American influence over this route ensures continued control of shipping lanes connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. In a similar vein, Trump’s Greenland proposal is not only about mineral access; it may also be about Greenland’s position along what could become a vital Arctic trade corridor.

These moves highlight a modern mercantilist approach to trade—one that prioritizes securing resources and controlling trade routes as a means of sustaining economic dominance.

The Risk: Mercantilism as a Catalyst for U.S. Trade Isolation

However.

While mercantilist policies aim to enhance national economic power, they also carry significant risks in the context of the modern global economy. By prioritizing domestic industry at the expense of international trade relationships, particularly in the presence of current trade finance, logistics, communications and business management options, the U.S. is incentivizing its trading partners to seek alternatives, thereby reducing their dependency on American markets.

This shift is further reinforced by the gradual move away from U.S.-based trade and financial settlement mechanisms such as the SWIFT system (PGTS). As nations explore alternative financial networks, U.S. influence through trade sanctions and measures which limit access to systems such as the SWIFT system will be further weakened..

America’s current trade partners may have much to gain from diversifying away from the U.S. Consider the potential impact if countries currently engaged with the United States redirected even 15% of their trade away from the U.S.[2] this would free up approximately $1 trillion to be reallocated across other trading partners. Emerging trade corridors—such as China’s Belt and Road Initiative, intra-Asian trade agreements, and expanding South-South cooperation—are already fostering a more decentralized global trade landscape.

Within the European Union and Asia-Pacific, over 60% of trade already occurs within the region (PGTS). In contrast, Latin America and the Caribbean conduct less than 25% of their trade within their own region, with a significant portion linked to U.S. markets. While this makes them highly dependent on U.S. markets it also presents a significant opportunity. LATAM and Caribbean economies could benefit substantially from increasing and diversifying their intra-regional trade, reducing their reliance on American imports and exports.

Strategies for Businesses to Navigate and Thrive

For businesses outside the U.S., adapting to these shifting trade landscapes requires proactive adjustments.

The logic for doing so can be drawn from the decline of mercantilism in the 19th century. The rise of industrialization, diversification of supply chains, and the emergence of free trade—particularly after the publication of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations (1776) (Shortform)—led to the eventual repeal of mercantilist policies such as the Corn Laws (1846) and The Navigation Acts (1849) – both of which were poster children for this model of trade policy.

Modern mercantilism will force many companies to reassess their current – comfortable and often complacent – views on market exposure. Companies should reassess their exposure to the U.S. and explore alternative trade and supply chain strategies as a means of de-risking their futures. Options to consider could include:

- Diversify Trade Partnerships – Expand market access in Europe, Asia, and Latin America to reduce reliance on U.S. trade policies.

- As a Canadian it has been embarrassing to have my colleagues in Asia suggest we must be “very comfortable” in our existing relationship with the American market, as the interest in entering and investing in new markets is so limited when compared with their discussions with regional or European partners. We have been coasting… Which is never a good place to be if you are looking for an economy known for innovation or productivity.

- Leverage Regional Trade Agreements & Trade Blocs – Take advantage of agreements such as the CPTPP, ASEAN Free Trade Agreement (AFTA), the African Community Free Trade Area (CFTA, and regional trade blocs like Mercosur and CARICOM.

- In developing a Market Entry strategy, my experience has been that regional agreements and trade blocs signal market priorities, while also providing Exporters with a focused and informed community of regional partners.

- Invest in Supply Chain Resilience – Secure diverse suppliers to minimize exposure to U.S. tariffs and trade restrictions.

- This strategy goes both ways. You are either securing diversity in your supply chain, or providing it to someone else.

- Capitalize on Emerging Trade Routes – Position businesses to benefit from evolving logistics networks, including Arctic shipping lanes and alternative transit and break of bulk hubs.

- In nearly every region of the world where I have been engaged recently, one of the single largest priorities is the creation or strengthening of regional trade corridors through investments in physical infrastructure, trade policies, technology and capacity building.

- Enhance Competitive Advantage Through Innovation – Focus on technology, sustainability, and product differentiation to build resilience against policy-driven trade disruptions.

- My experience with International Product Development and Innovation has been these changes are typical incremental, and driven by a moment of crisis or a moment of inspiration. Diversification into new markets may begin with crisis but will inevitably open the door to inspiration as you engage with new markets and new ideas.

Conclusion

Trump’s mercantilist approach to trade policy is reshaping global commerce, with lasting implications for supply chains, resource control, and international alliances. While such policies may aim to strengthen the U.S. economy, they also create opportunities for other nations to step in and redefine global trade patterns. By proactively adapting to these changes, businesses outside the U.S. can not only mitigate risks but also find new pathways for growth in an increasingly decentralized global trade environment

[1] Modern mercantilism has taken many forms over the years. China’s use of mercantilist strategies as part of its broader economic policy is a topic worthy of its own discussion. However, it is also important to recognize that the first Trump administration actively pursued “America First” mercantilist policies (Carnegie Endowment). One key takeaway as we assess the current situation, is that modern trade practices, international relations, and global supply chains may be more resistant to blunt mercantilist tactics than their 18th-century counterparts.

[2] The US Census Department suggests total value of U.S. international trade—comprising both exports and imports—was approximately $7.3 trillion in 2024. Of this figure, imports represent $4.11 trillion, and exports represent $3.19 trillion. ( https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/Press-Release/current_press_release/ft900.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com )

One thought on “Trump and Mercantilism: Implications for International Business”